Is Cybercrime a Global Phenomenon That Is Not Restricted by Geographical Boundaries?

As the usage of computers and the Internet has significantly increased in recent decades, so has the rate of cybercrime. It is argued that cybercrime is a global phenomenon and overcomes geographical boundaries that many other forms of crime are bound by.

The Internet has been a catalyst for enabling people to join communities where they’re not physically connected but are able to be virtually. In many senses this has seemingly enabled the world to shrink into a single community when online. Criminals are able to take advantage of this single online community too; the potential number of cybercrime victims is now bound by the number of computers that are connected to the Internet, whereas the number of potential victims for traditional crime is very often bound by geographical reach.

Cybercrime is often delocalised too; the causes and consequences of the crimes are not confined to the same geographical location. For example, the perpetrator may execute the crime from somewhere remotely to where the consequences of it are felt. An example of this is the Stuxnet worm which was developed to attack SCADA systems and specifically designed to cause substantial damage to Iran’s nuclear program. Stuxnet is widely reported to have been developed jointly by the USA and Israel, highlighting how geographical boundaries did not restrict the ability for the attack to be carried out effectively.

If we look back just 20 years, the vast majority (~95%) of Internet users were residents in the USA or allied countries. This meant that the Internet was able to be controlled by governments that had the motivation to do so until the early 2000s. Serious computer crimes that took place were able to be investigated and criminals were able to be identified and subsequently prosecuted with relative ease. Many argue that this meant that geographical boundaries were still able to be enforced on the Internet. However, accessibility to the Internet began to increase and in parallel the cost of technology reduced. As a result, the number of people on the Internet from around the world increased exponentially. This internationalisation of the Internet caused geographical boundaries to be removed and so cybercrime also began to defy traditional territorial jurisdiction.

Furthermore, online currency such as the cryptocurrency Bitcoin, is another example of how the Internet has removed geographical boundaries. Currency is traditionally very much jurisdiction based and specific currencies will only be accepted as legal tender in specific jurisdictions, as permitted by the law. However, online currencies such as Bitcoin are widely accepted over the Internet and thus all over the world. This type of currency is also being utilised by cyber criminals. For example, it is commonly used to collect payments as part of ransomware attacks.

Globalisation is the process by which people, organisations and governments worldwide become increasingly interconnected. The Internet and subsequent rise of e-Commerce has made this a reality for all businesses, no matter how big or small. It is clear to see that cybercrime is also a beneficiary of globalisation too. Globalisation in cybercrime is able to be seen from many angles and some of the points made above also refer to this. There are some other aspects of globalisation which also benefit cyber criminals though; in general people have become more comfortable with interacting and trading with people or organisations whom they have no previously established relationship with. For example, it is now common practice to trust businesses online and purchase things off of them where an already established relationship does not exist. Cyber criminals are able to take advantage of the inherent trust that exists on the Internet and thus are better able to social engineer individuals and commit cybercrimes. Additionally, cyber criminals are able to disassociate themselves with the crimes that they commit online, as they are operating in one big society which provides them with a greater sense of anonymity.

Globalisation of cybercrime has also caused governments to have to start to think about how they are able to tackle it from global perspective. The UK government have published documents which state that they are working closely with other countries to try to build out standards and policies to ensure a standardised approach to tackling cybercrime. This will be seen by many as governments recognising cybercrime as a global phenomenon and not something that is able to be controlled solely by traditional geographical jurisdictions.

However, there are many arguments why cybercrime is to some degree restricted by geographical boundaries. Law is very much jurisdiction based and anyone that has been prosecuted for cybercrimes will have been done so within a legal jurisdiction which inherently has defined geographical boundaries. For example, Kane Gamble, who committed an offence against U.S. government chiefs was charged by the UK courts under the Computer Misuse Act, even though the consequences of the crime he committed occurred in the USA. In addition to this, Lauri Love was another British citizen who hacked into government computers in the USA. The USA attempted to extradite him to face trial there however, this was overturned by the UK courts. This represents another example of how there are still strong jurisdiction and geographical boundaries when it comes to prosecuting cybercrime.

Moreover, with the exception of the Computer Misuse Act the majority of laws used against criminal offences which take place online are prosecuted using traditional law; law that was not developed specifically for computers or the Internet. For example, crimes such as impersonation of people or organisations which are often utilised by cyber criminals when carrying out social engineering attacks, would if prosecuted be charged as forgery. This demonstrates again that in the eyes of the law, cybercrime is not inherently different from traditional crimes and very much geographically bound.

In addition, we also have seen other examples that geographical borders exist on the Internet. Online streaming sites, for example Netflix, will restrict the ability for consumers to watch certain films and TV shows depending on the country that you are connecting from. This certainly illustrates that the Internet is somewhat restricted by geographical boundaries.

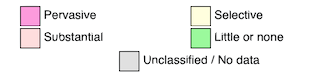

Finally, censorship of the Internet is something that occurs in many jurisdictions across the world. For example, countries such as China enforce very stringent censorship on the Internet. As well as this, France and Germany block content related to Nazism and Holocaust denial and many countries around the world block content such as child pornography and hate speech. This element of control and suppression of content on the Internet is another case that illustrates the existence of geographical borders.

Ultimately, I believe that there are many points that illustrate that the geographical boundaries that may inhibit the actions of criminals carrying out traditional crimes, do not affect criminals committing cybercrime offences in the same way. Crime that takes place on the Internet certainly has the ability for a far greater reach of victims and it is often possible in a much shorter space of time. Additionally, it would seem that governments and law enforcement organisations across the world are still trying to work out the best way to police the Internet. It appears that they also recognise that this is not able to be successful unless there is a more cohesive global effort. However, there is still strong evidence that the Internet does not completely remove geographical borders too. This is especially true when it comes to Internet censorship and the enforcement of law; these are both very much bound by geographical borders.